Some of us don’t like hierarchies. To be specific, and to give a little sneak preview, Red and Green don’t like them, but Blue and Orange do. Tier 2 levels, Yellow and Turquoise, can live with them when used appropriately.

I have no idea what you are talking about.

I know. In the next several posts, we will discuss development theories, bringing us to the first controversy we must confront about Integral Theory: hierarchies.

The Hierarchy Controversy? Oh no!

Yep. Here are the issues:

Verticality: Hierarchy models are usually displayed and explained as vertical models and vertical models use terms like altitude and higher and lower. It is easy to imply better and worse from these terms, and when it comes to growth and development, better and worse can be confused with more or less worthy of love or respect. I prefer using “earlier and later” stages or levels.

Power: Hierarchies in organizations denote relative power. Since power can be abused, we are often wary and self-protecting when working in or with power hierarchies. We can undoubtedly misuse developmental hierarchy schemes to label people in harmful ways. Still, when used with care, the theories can enhance our sensitivity and appreciation for those at each level. To automatically dismiss development theories is to overlook scientifically validated models, often rooted in the world’s wisdom traditions and mind-expanding in ways we can use to create new, all-embracing worldviews of our fellow humans. Instead of looking up or down at others, we see them at different points on the same growth path we are traveling.

Growth: In Glimpsing Integral, I am not referring to Power hierarchies. Unless otherwise noted, my stipulated definition1 for hierarchy in this Substack is Growth hierarchies that have been described in development theories. Here are the ways they differ from power hierarchies:

Our capabilities grow in response to the challenges of the environment or the goals we set. If you move to France and learn French, you must increase your language and cultural capabilities while retaining your previous language skills. If we avoid new circumstances (geographic, cultural, religious, educational, vocational, etc.), we do not experience the conditions that stimulate growth.

Developmental theories view the differences we sometimes view as moral or ethical defects in a new way. They reframe them as values and norms that make sense in the context of earlier worldviews. For example, we can share our resources as our worldview becomes more inclusive of others.

As we will learn in the Lines element of Integral, people proficient in one line (or ability, intelligence, or view) are not equally developed in others. For example, we often expect intelligent people to be more kind or better communicators, but that is sometimes untrue.

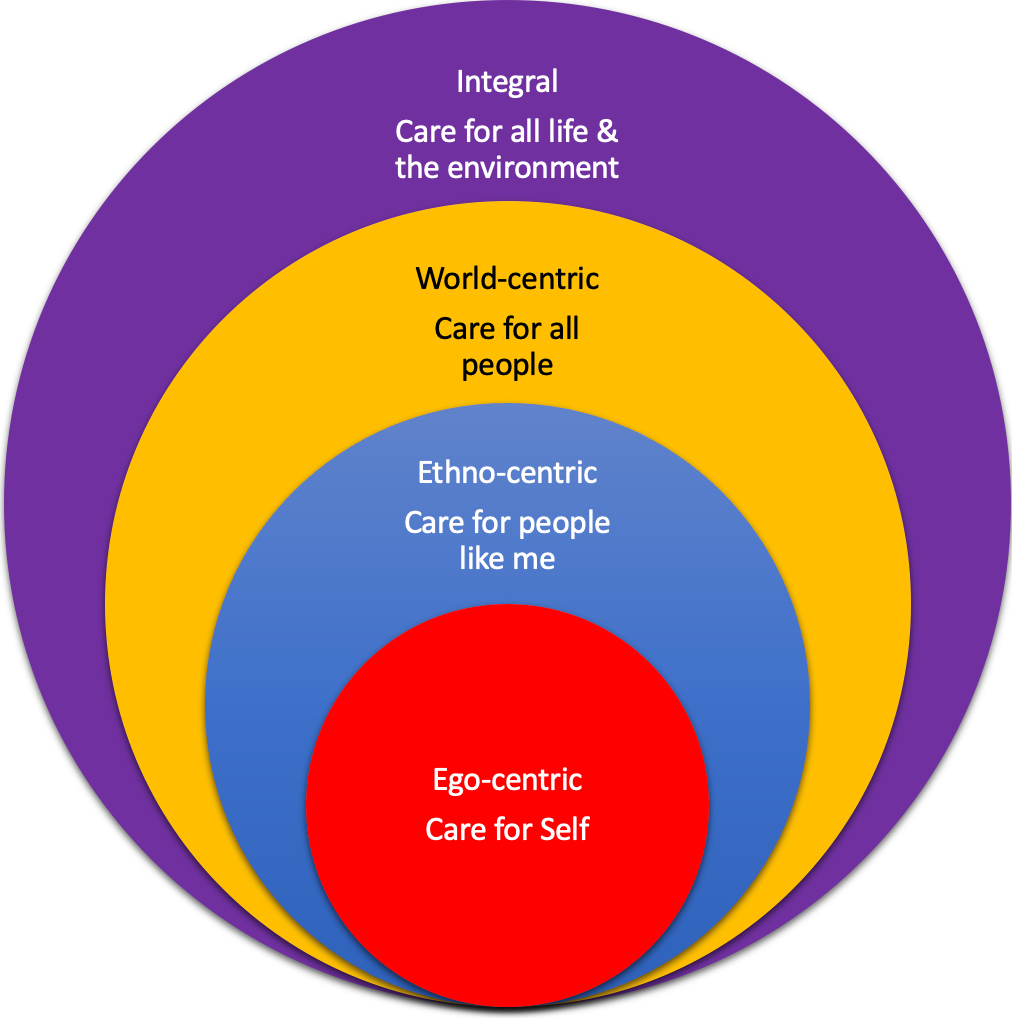

In a growth hierarchy, we transcend and include the characteristics of previous levels. Development models are often displayed as ladders or stairs. I like the visualization shown below. Earlier levels are included in later levels, and later levels transcend previous levels.

I need to let this perspective sink in for a while. I’ll let you know if I have questions.

Concern about hierarchy is natural, so don’t hesitate to bring it up. The instinct to throw out all hierarchies is based on misunderstanding patterns that repeat themselves throughout nature. After all, a sprout is not more elite than a seed but is more developed in its growth toward maturity. (Updated 6.19.23, 2.19.24, 9.2.24)

A stipulative definition occurs when an author specifies how a particular word or phrase is being used in their context, often giving it a specific meaning that may differ from its standard or commonly accepted usage. This allows the author to clarify how the term should be understood within the context of their writing.